Week in Review: Why the existing home sales number was so lousy.

Last Friday’s Existing Homes Sales data from the National Association of Realtors was nothing less than awful. Sales fell 1.5% month-over-month and 34% year-over-year to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 4.02 million. This was lower than the pandemic-driven nadir in 2020 and you would have to go back to the housing collapse of 2008 to see similar numbers. Unlike the housing crash of yesteryear, the inventory of homes for sale is too low, not too high. There were only 970,000 homes for sale, which is extremely low by historical standards. So, it isn’t like there is a glut of homes flooding the market, we have a shortage. Affordability issues would imply high prices, and high prices should bring sellers out of the woodwork. But that isn’t happening because this isn’t about prices - it is about rates.

December’s home sales were probably negotiated in October, which was the peak of mortgage rates in 2022. The 30 year fixed rate mortgage averaged about 6.9% during the month of October which was the highest since 2002.

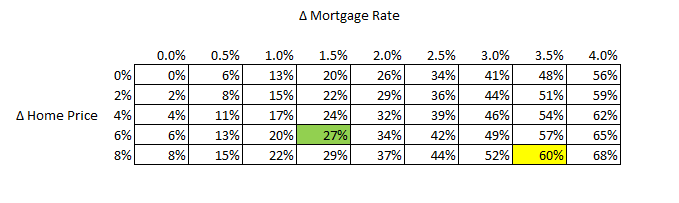

The difference between January 2022 and October of 2022 in terms of affordability is pretty stark. Below I created a matrix showing how increases in mortgage rates and house prices affect the monthly mortgage payment. According to the FHFA House Price Index, home prices rose by about 8% between January and October. The mortgage rate at the beginning of the year was 3.5% and it ended October around 7%. This corresponds to an increase in the mortgage rate of 3.5% and an increase in home prices of 8%, which jacked up the principal and interest payment by 60% which is represented by the yellow square.

If you look at the changes since October, the mortgage rate has fallen about 1% and home prices have fallen about 2%. This would equate to the 2.5% / 6% block which makes the difference between Jan 2022 and today about 42%. It is still a high number, but nowhere near where things were in October. Can this fall further? I think so.

There are two big inputs into mortgage rates: long term rates and MBS spreads. The 10 year is the benchmark yield people generally use for mortgages, and it is independent from the Fed Funds rate which the Fed sets at its periodic meetings. MBS spreads are based on where mortgage backed securities trade in the market and they are the basic input to the rate Rocket or Chase quotes you on any given day.

The difference between these securities and Treasuries is called the MBS spread, and it varies over time. Sometimes mortgage rates will be a lot higher than Treasuries and sometimes they will be very low. MBS spreads fluctuate over time based on the relative value judgements of pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and bond funds. These folks are always comparing the potential returns of mortgage backed securities versus other similar assets such as investment grade corporate bonds, commercial mortgage backed securities or municipal bonds and are always adjusting their portfolios to find the optimal mix to get the best return for the least amount of risk.

I plotted the difference between the prevailing 30 year mortgage rate and the 10 year Treasury yield over time and it paints a decent picture of what has been going on for the past year. This chart is a proxy for MBS spreads - MBS spreads are super-complicated and a MBS trader would certainly object to this - but this is good enough for an explainer of what is going on.

This chart goes back to 1990. The first thing to note is that the difference in late 2022 was a record level of 2.9%, which corresponds to a mortgage rate of 6.9% and and 10 year of about 4%. The last time we saw similar spikes was during the early days of the COVID pandemic and the 2008 financial crisis. The average since 1990 has been 1.7%. This means that if MBS spreads revert to the historical average we could see another 1.2% drop in mortgage rates even if the 10 year goes nowhere. These spikes generally don’t last long.

If you look at where we are today, the 10 year bond yields about 3.5% and the Freddie Mac 30 year fixed rate mortgage is 6.15%. This makes the spread about 2.65%, which is still super high, but not as bad as October-November. This also means that there is another 1% potential drop in mortgage rates, even if the 10 year bond yield goes nowhere. This would correspond to the green square. Remember rates affect sellers too, and many will decide to stay put and keep their 3.5% mortgage rate. Moving up from a 3.5% rate to a 7% rate is daunting, but maybe going from 3.5% to 5% isn’t.

Just as an aside, a change in home prices isn’t necessary to do the heavy lifting here. The affordability issue is much more a function of rates than prices. Which makes sense - as any car dealer will tell you, people focus on the monthly payment and not the sticker price. That said, I wouldn’t fall out of my chair with shock if home prices declined a mid single-digit percent on average next year.

The thing that surprised me when I created this chart is that MBS spreads during the period of quantitative easing (QE) weren’t much different than spreads before QE. The shaded blue part of the chart shows the period of QE where the Fed was buying MBS in the market. Part of what has been weighing on the MBS market has been the fear that the Fed is going to sell its massive holdings which could collapse MBS pricing. This probably can’t happen for technical reasons. MBS liquidity is binary and narrow based on prevailing mortgage rates. There is a mismatch between the rates the Fed owns and the rates that are actively trading in the market. The rates the Fed owns (3.5% or so) don’t trade so it couldn’t sell them even if it wanted to. No buyers.

Aside from the financial crisis period, the last time we saw major MBS underperformance (i.e. wider spreads) was the late 90s when people wanted to buy Yahoo on a price-to-pageview metric and no one wanted a stodgy old MBS. QE didn’t have that big of an impact on MBS spreads in the first place, so I can’t imagine QT (quantitative tightening) will either.

Which brings us back to existing home sales. If mortgage spreads revert to the mean, the affordability problem improves quite a bit. The other side of the affordability coin, which I didn’t spend any time on here - is wages. Wage inflation will go a long way to fixing the affordability problem although it will take longer. That said the December existing home sales number is probably the bottom for the real estate market.