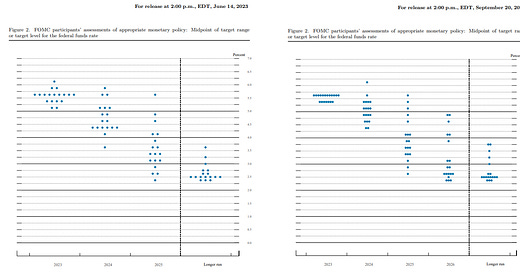

As expected, the Fed decided on a hawkish pause at the September FOMC meeting. Even though the Fed didn’t hike rates, it still signaled that it sees another rate hike this year and the dot plot poured cold water on big rate cuts next year. The dot plot comparison is below:

I calculated the expected rates based on individual dots. The forecast for 2023 was pretty much unchanged. The expectation for 2024 was increased by 30 basis points, from an average of 4.75% to 5.05%. The forecast for 2025 increased by 19 basis points, from 3.78% to 3.97%.

The economic forecasts bumped up expected GDP growth and lowered the unemployment forecast. Inflation expectations were more or less the same, although core PCE inflation this year was revised downward. Jerome Powell took quite a few questions regarding the incongruence of higher rates going forward with lower inflation forecasts. His explanation was that the neutral rate for the Fed Funds rate (r-star) might be higher than previously thought. This means that the Fed’s estimate for the non-inflationary interest rate might have increased.

What does the Fed decision mean for mortgage rates? While the decision to keep rates elevated is not great for MBS in general, it should point to reduced interest rate volatility in the future, which should be supportive for lowering MBS spreads. MBS spreads are the incremental yield that investors require in order to be indifferent between holding MBS are Treasuries.

For all intents and purposes, mortgage backed securities issued by Fannie Mae / Freddie Mac and guaranteed by Ginnie Mae don’t have credit risk. Regardless of whether the borrower makes his or her monthly payment, the investor still gets paid the principal and interest on time. This is because the servicer makes the payment if the borrower cannot.

So if a mortgage backed security yields 7% and a similar Treasury yields 5%, why would investors choose the Treasury over the mortgage backed security? If there is no credit risk, then why choose to make 5% when you can get 7%? The difference is that mortgage backed securities have an embedded option that Treasuries do not have. This is the prepayment option which is the right of the homeowner to pay off the mortgage early without penalty. It is similar to a call right on a corporate bond.

Since the prepay option is owned by the borrower, the investor is short the prepayment option. That prepayment option is a big driver of the difference between yields on mortgage backed securities and the yield on Treasuries. It makes mortgage backed securities much more sensitive to changes in interest rates.

Options like the prepayment option have volatility as an important input. Volatility correlates with option value, which means that higher volatility makes the option worth more. Since the MBS investor is short this option increasing volatility makes mortgage backed securities worth less than Treasuries of comparable maturity. Bond market volatility is the enemy of MBS investors.

This means that MBS spreads correlate reasonably well with bond market volatility as measured by indices like the BAML / ICE MOVE Index. The big driver of bond market volatility over the past 18 months has been uncertainty around monetary policy. Once this uncertainty disappears, we should see a meaningful decrease in MBS spreads due simply to the market repricing the prepayment option.

Below is a chart of bond market volatility: the spike in volatility correlates with the liftoff, where the Fed started hiking the Fed Funds rate.

Compare the chart above to MBS spreads below:

The two charts seem to correlate reasonably well. Ultimately, these two charts show that bond market volatility and MBS spreads correlate and revert to the mean. If we get a reversion to the mean in MBS spreads, it means we could see mortgage rates in the low 6s, even without the 10 year yield moving lower. MBS spreads have begun to “fade” the move in the 10 year, which means they have fallen slightly in September despite the spike in the 10 year yield. This is typical - MBS yields often lag moves in the 10 year.

While things are absolutely dismal in the mortgage banking space, and everyone is bleeding cash, we might get some relief as the Fed at least gets out of the way. There has been talk about who might be the marginal buyer of mortgage backed securities if the Fed is no longer doing it. The fear is that mortgage rates will stay high if the Fed isn’t buying.

I would point to the chart above - look at MBS spreads between 2012 and 2020 and compare them to the pre-bubble era. The difference is not all that meaningful. If the Fed wasn’t able to meaningfully push down spreads when it it was buying $40 billion a month, it is hard to see how letting it run off will have a major impact.

Better days for the mortgage space are coming, but the fourth quarter looks to be dismal as the seasonal home purchase season is months away and refi opportunities are few and far between.